Sleep Quality and Chronotype of Young Athletes Addicted to Smartphones During Ramadan Observance

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Problematic smartphone use is associated with social, physical, and mental health issues, including chronotype and sleep patterns. During Ramadan intermittent fasting, these factors were more affected. However, no study explored problematic smartphone use and sleep patterns during Ramadan. Thus, the present study explored problematic smartphone use, sleep patterns, and chronotypes among athletic sample during Ramadan and assessed their relationship.

Methods

Fifty athlete students (18.44±0.79 years) were voluntarily involved in this prospective cohort study. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) were used to collect information on sleep quality and circadian preferences, respectively, before one week of Ramadan (baseline). Then, the participants repeated the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and completed the Arabic version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale short version (SAS-sv) at the end of Ramadan.

Results

Of the 50 patients, 38% of the participants demonstrated problematic smartphone use. Ramadan showed no significant impact on sleep quality. Problematic smartphone use was not associated with sleep quality or chronotype. Nevertheless, it was negatively correlated with chronotype.

Conclusion

High prevalence of smartphones and sleep quality was reported during Ramadan. The associations between sleep quality and problematic smartphone use were not confirmed. However, there is a negative relationship between chronotype and problematic smartphone use. The study suggests more focus on how athlete students can exploit physical exercise as a healthy alternative to keep control of excessive use of smartphones.

INTRODUCTION

It is difficult to imagine our life without smartphones. For collegial students, the smartphone is an indispensable companion. However, their overuse can cause a wide range of problems. Indeed, problematic smartphone use (PSU) refers to excessive smartphone use or dependence in daily life, coupled with impairments and signs similar to substance use disorders [1]. The smartphone addiction becomes problematic for public health, as reported by the World Health Organization [2]. Previous studies revealed that there is a significant association between excessive use of smartphones and anxiety [3], stress [4], depression [5], musculoskeletal pain [6], and worse physical fitness (i.e., headaches, fatigue, dizziness, tension, memory loss, and hearing loss) [7]. Moreover, extensive evidence demonstrates the link of PSU with sleep quality [8] and chronotype [9,10]. Another research study revealed that using mobile phones before bedtime increases exposure to light, deregulating the circadian system, and increasing psychological stimulation, thus delaying sleep onset [11].

On the other side, during Ramadan intermittent fasting (RIF), student-athletes abstain from eating, drinking, and sexual activities from sunrise to sunset [12]. They eat only overnight (breakfast at sunset and suhur before dawn) [13]. As a result, several changes were observed in sleep patterns [14], eating schedules [15], potentially impacting dietary intake [16], body weight [17], chronotype [18], and physical fitness [14].

So, the RIF and PSU share similar associate factors, mainly decreased sleep quality and circadian alteration. A recent study revealed that sleep problems can boost brain vulnerability and lead to dependence [19]. Thus, we hypothesize a possible relationship between the risks of PSU, sleep quality, and circadian preferences.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has examined the relationships between these particular factors during RIF, as the majority of studies in the field of PSU have only focused on daily life. As a result, the current study explored the sleep quality and chronotype of young athletes addicted to smartphones during RIF. Indeed, the primary objective was to identify the relationship between PSU and the sleep quality of athlete students during RIF. Then, the secondary objective was to verify the potential association between the chronotype and PSU during Ramadan. We hypothesized that PSU is associated with sleep quality but not chronotype.

METHODS

Participants

Fifty athlete students (age 18.44±0.79 years, body mass index [BMI] 21.2±2.77 kg/m2) were voluntarily involved in this research protocol. None of them were illnesses or smokers. All were athletic students at the college. All participants were engaged in regular physical activity at their college (at least 10 hours per week) and were members of local sports teams. They were requested not to modify their diet and to maintain a normal lifestyle. The study was approved by the ENS-C Ethics Committee (IPR: 0043/2021), and it was conducted according to the Code of Ethics for Human Experimentation of the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki [20]. All participants were informed about the experimental design and provided written consent to participate before the intervention.

Measurement instruments

After a familiarization session, the sociodemographic and anthropometric evaluation of body mass (kg), height (m), and BMI (kg/m2) was collected. Following that, information on chronotype and sleep quality was obtained using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [21] and the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) [22] in a prospective cohort design before one week of Ramadan (baseline). Then, the participants repeated the PSQI and completed the Arabic version of the Smartphone Addiction scale short version (SAS-sv) [23] at the end of Ramadan. The study was carried out in Morocco in 2022. Ramadan started on April 3 and finished on May 2. The temperature reached up to 21°. The minimum seasonal temperature is 14°. The average fasting duration was 15 h 30 min.

PSQI

The PSQI is a self-report questionnaire used by researchers to assess the subjective sleep quality of the population [21]. It comprised 19 questions, measuring 7 different aspects of sleep to distinguish between “poor” and “good” sleep. A total of 5 or higher indicates poor quality of sleep. Researchers deployed the validated Arabic version in this research, which has shown to be reliable enough (Cronbach’s alpha value=0.77).

MEQ

It is a self-evaluation questionnaire created by Horne and Östberg in 1976 [22]. It is used to identify human circadian typology. Based on the total MEQ scores, the researchers identified the sample chronotype as evening type (16–41), morning type (59–86), or neither type (42–58). In the current study, 4 academics independently translated the questionnaire into Arabic. Then, we conducted a trial study two times (30 days’ time difference) with 30 participants to determine if the questionnaire was comprehensive. Then, we apply the questionnaire to the study. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the first and second applications were 0.77 and 0.73, respectively.

SAS-sv

The SAS-sv consists of 10 items, each one rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 6 (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). The total score varies from 10 to 60. Higher scores indicate a risk of “smartphone addiction.” The threshold score for females is 33 and 31 for males [24]. In the current study, the researchers employed The Arabic version [23], which showed an excellent internal consistency (α=0.87).

Statistical analysis

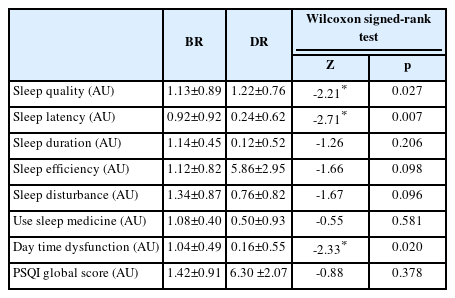

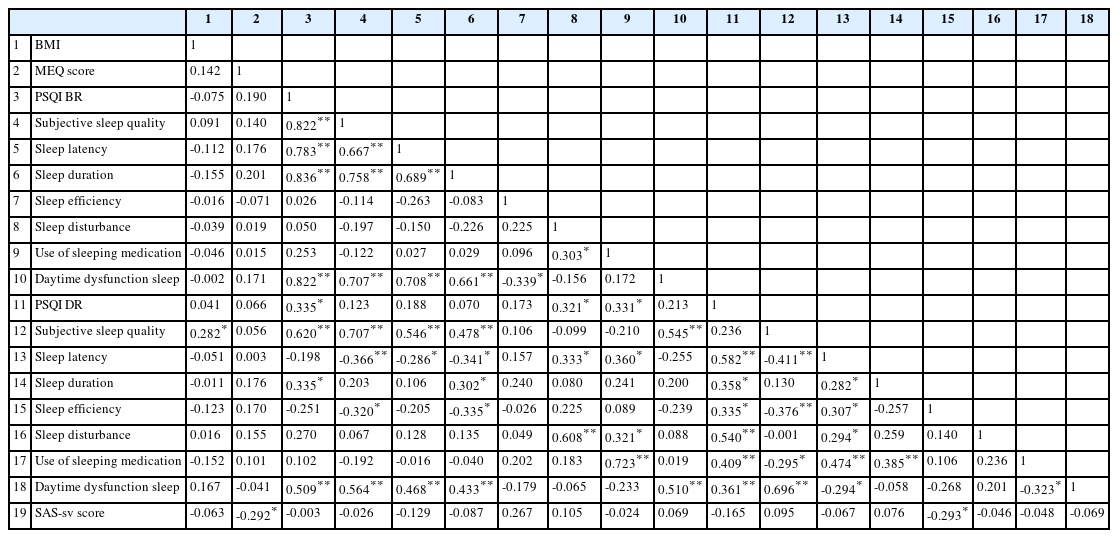

Data were statistically analyzed using the SPSS Statistics for Window (ver. 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables are given as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables are given as numbers and percentages. The normality of distribution was assessed by using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The nominal or categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared (χ2) test. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), independent-samples t-test, and a Kruskal-Wallis H were used to explore the significance of differences among means. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to identify the difference in means before (BR) and during Ramadan (DR). For the correlation, we used the Spearman correlation. We decide on significance only if the p-value is less than 0.05.

RESULTS

The study included 50 athletes (19 females, 31 males) students from Morocco (age 18.44±0.79 years; BMI 21.21±2.77 kg/m2). The total SAS-sv score of participants was 30.22 (±10.10). The descriptive characteristics of the participants are given in Table 1. Indeed, the Pearson chi-square showed that there is no statistically significant association between SAS-sv and gender, chronotype, PSQIBR, PSQIDR, and sports categories (χ2=3.311, p=0.069; χ2=3.891, p=0.143; χ2=0.053, p=0.817; χ2=2.782, p=0.095; χ2=4.812, p=0.090). Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the differences in sleep quality before and during Ramadan. Detailed results are presented in Table 2. The data showed no significant difference RESULTS The study included 50 athletes (19 females, 31 males) students from Morocco (age 18.44±0.79 years; BMI 21.21±2.77 kg/m2). The total SAS-sv score of participants was 30.22 (±10.10). The descriptive characteristics of the participants are given in Table 1. Indeed, the Pearson chi-square showed that there is no statistically significant association between SAS-sv and gender, chronotype, PSQIBR, PSQIDR, and sports categories (χ2=3.311, p=0.069; χ2=3.891, p=0.143; χ2=0.053, p=0.817; χ2=2.782, p=0.095; χ2=4.812, p=0.090). Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the differences in sleep quality before and during Ramadan. Detailed results are presented in Table 2. The data showed no significant difference between the total score of PSQI between the two measures (Z=-0.88, p=0.378). However, we found a significant difference in subjective sleep quality, latency, and daytime dysfunction. The independent-sample t-test showed no difference in risk of PSU based on on sex or PSQI during Ramadan [t(48)=0.162, p=0.872); t(48)=-1.584, p=0.120, respectively]. One-way ANOVA analysis showed no significant difference in SAS-sv means between circadian preferences [F(2,47)=2.618, p=0.084] and sports categories [F(2,47)=0.796, p=0.457]. A Kruskal-Wallis H test showed that there was no significant difference in sleep quality (before or during Ramadan) between the different circadian preferences respectively [χ2BR(1)=0.220, p=0.639; χ2DR(1)=0.198, p=0.656]. However, the Spearman correlation showed a significant negative correlation between the chronotype and SAS-sv (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The current study explored the sleep quality and chronotype of young athletes addicted to smartphones during RIF. As result, PSU revealed no significant relationship with gender and sleep quality during RIF, but we detected a negative correlation between the chronotype and PSU.

Firstly, we found that the risk of PSU is not associated with gender during Ramadan. This result is consistent with data from an Egyptian study confirming no gender difference among smartphone addicts [25]. Also, the same confirmation was published in a cross-sectional analytical survey in Taiwan in 2023 showed no link or association between PSU and gender. Contrary to our finding, other researchers found a significant association [24], and females are more addicted than males [26,27]. However, other studies have found higher scores for males than females [28]. Such findings are controversial and may be attributed to socioeconomic factors, Internet accessibility, cultural norms, and other health factors that vary according to gender and location [29].

Secondly, the study found that Ramadan does not affect the sleep quality of athlete students. Our result is consistent with a recent systematic review published in 2021 which found that the global score of the PSQI increased from 4.053 pre-Ramadan to 5.346 during Ramadan, without any statistically significant [30]. However, other studies confirmed that athletes’ sleep quality deteriorated during RIF [14]. As an explanation for this reduction, Nakajima [31] in 2018 reported that sleeping with a full stomach can cause reflux of the stomach and reduce diet-induced thermogenesis, thus impairing sleep quality.

From our results, PSU revealed no significant relationship with sleep quality during RIF. Contrary to our expectations, previous findings have revealed a significant association between excessive smartphone use and sleep problems such as reduced sleep quality, daytime fatigue, delayed sleep onset, and reduced sleep duration [32,33]. This significant result is probably linked to using cellular phones before bedtime, which increases exposure to light, disrupts circadian function, and increases psychological stimulation, which delays sleep onset and induces excessive smartphone use [11]. Generally, the evidence for the negative effects of excessive smartphone use on sleep is increasing [34]. So, it is beneficial for athletic students to change negative behaviors by following special programs to be aware of excessive smartphone use.

However, the current study detected a negative correlation between the total score of MEQ and SAS-sv. These findings support a recent study that found behavioral addictions like PSU, and Internet addiction can be associated with E-type [9]. Moreover, people with evening type tend to smoke, consume alcohol, and use other illicit substances [35]. Generally, circadian rhythms are also affected by various technological devices (smartphones and computer screens) [36]. These observations may be related to the disruption of melatonin levels by smartphones’ blue light, causing sleep quality impairment [37], and shifting the chronotype to the evening by causing later bedtimes [36]. It is also possible that the nocturne ritual of Ramadan may contribute to this shift.

It should also be noted that the present study has some limitations. Firstly, the sample size was modest, and a larger prospective cohort design is needed to increase the generalizability of the results in future studies. Secondly, the research was conducted with self-report methods, which can be biased and impact the data quality. We recommend using more objective methods. Lastly, PSU can be caused by other factors (i.e., emotion, personality, socioeconomic level). These factors need to be taken into consideration in future research.

As a recommendation, future studies should focus on how athlete students can exploit physical exercise as a healthy alternative to keep control of PSU and improve their sleep quality among passive students.

In conclusion, the present study showed that Ramadan did not affect sleep quality. Also, the prevalence of PSU in athlete students during Ramadan was high. Unlike our hypothesis, PSU was not significantly associated with sleep quality and chronotype. Nevertheless, we showed that PSU is correlated negatively with chronotype. These results suggest the need to provide Moroccan students with coping strategies that would help them to prevent PSU and reduce its high prevalence.

Notes

Funding Statement

None

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Data curation: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Formal analysis: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Investigation: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Methodology: Anas El- Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Software: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Visualization: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Writing—original draft: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Writing—review & editing: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi.