Pathophysiology of Memory Inception and Retrogression and Clock Dependent Divergence in Cognizance

Article information

Abstract

Our body (mammals) has a direct connection with the earth’s axial cycle, which is similar to the universal concept of phenotype, representing the result of genotype-environment interactions in all living organisms. Collectively, 24-hour phases of day and night are termed circadian rhythms. It corresponds with body clocks to adapt and optimize physiology according to the changes in the surroundings. Contemporary studies in vertebrate and invertebrate models have revealed circadian rhythms (time and light) affect neurophysiology and cognitive performance. However, a clear understanding of the underlying mechanism of the genetic, molecular, and complex process of memory formation is yet to be confirmed. In this review, we are focusing on the effects of the biological clock on memory inception and retrogression along with clock dependent cognizance.

INTRODUCTION

The body clock regulation is quite complex to describe in a simple manner. For instance, when the body is symbolized as a machine, that operates all of its staff in a synchronized way, continuously affected by the frame of time and light propensity. As a result, environmental factors such as light and darkness, as well as the body clock (endogenous circadian rhythms) work in unison to improve hemostasis, including the cell cycle, body temperature, feeding, metabolism, and, perhaps most importantly, the sleep-wake cycle as well as memory formation and consolidation [1].

Physiological, biological, and behavioural processes in mammals are regulated by circadian rhythms. The endogenous biological clock is located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN), a small group of hypothalamic nerves, recognized as the master circadian pacemaker. It is positioned unswervingly above the optic chiasm [2,3] synchronically and functionally regulates the circadian rhythms of mammals throughout the 24-hour oscillations and secures every essential physiological process [4,5].

In the 1970s, the role of SCN to drive the circadian rhythm was coined for the first time, but the molecular basis of the effects on physiology and behaviour in mammals finally became clear in the late 1990s. The SCN electrical activity and divergent state activity depend on circadian variations (day-night oscillation) [6]. Any unfavourable condition in SCN abolishes the regulatory mechanism. On the contrary, upon restoration of SCN, the circadian rhythms move smoothly [7-11].

REGULATORY MECHANISM OF SCN AND CLOCK GENE ACTIVATION

The photoreceptors of the retina are sensitive to light intensity. Expressed photopigment melanopsin is detected by the rods and cones as well as photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Upon receiving the processed–light/signals to the SCN via the retinohypothalamic tract, finally the intracellular molecular clock mechanism is activated through enhancement of positive (BMAL1 and CLOCK as activators) and negative [period (PER) and cryptochrome (CRY) proteins] elements [11,12].

Interaction between clock function and memory formation

As the body maintains clock dependent gene expression/activation/suppression, particular genes and genetic interactions are responsible for memory and memory formation. However, the original roles of local brain circadian clocks in memory formation remain unclear.

The molecular mechanisms facilitating circadian rhythm generation in the SCN are well studied: BMAL1 and CLOCK form a heterodimer and trigger the transcription of their target genes, including the period (PER1, PER2) and the cryptochrome (CRY1, CRY2) [13-18]. PERs and CRYs both genes inhibit the BMAL1/CLOCK-mediated transcription in a negative feedback loop, thereby generating circadian transcriptional rhythms [13,14].

Are clock genes being memory genes?

Drosophila melanogaster, a model organism, showed time-dependent eclosion rhythm depending on their strain. It proposes a genetic basis for the circadian regulation of this process, prompting a forward mutagenesis screen that identified the first clock gene, period (PER) [19-21]. Interestingly, these mutations cause correlative changes in the circadian locomotor activity rhythm in adult flies.

It is important to resolve the confusion about the relationship between the clock gene and memory formation. This relationship is strongly confirmed by the phenomenon where the clock gene independently forms memory and has roles in eclosion or the generation of circadian rhythms [22-26].

CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS AND MEMORY

The impact of time-of-day effects and circadian rhythms on cognitive performance and memory formation in humans [27-29] have been studied for decades, and there has been a renewed interest in this topic in light of an increased understanding of the genetic, molecular and systems-level events that underlie these complex processes [30-34].

Recent discoveries have shown a high level of integration between cellular signalling cascades [such as the cyclic AMP (cAMP), mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), and cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB)] pathway, that regulate circadian rhythms and memory processing. Disruption of circadian rhythms has negative consequences on memory and cognitive performance in various tasks and several species [35].

Functions of melatonin

Melatonin, the hormone of darkness (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine, MTG), had been first identified as the hormone of the pineal gland secreted into the cerebrospinal fluid, and it regulates patterns of sleeping and awakening in humans [36,37].

Over the past decade, melatonin’s impact on chronobiological effects has been vastly scrutinized. Remarkably, melatonin affects the firing rate of the mammalian SCN and hippocampal CA1 neurons [38-41]. Therefore, circadian hormonal modulation of neuronal firing could be a general mechanism throughout the brain.

As a signalling molecule, melatonin is widely expressed throughout vertebrate and invertebrate human, zebrafish (Danio rerio), sea slugs (Apylsia californica), mice (Mus musculus), and flies (D. melanogaster) [42-46] and is secreted in a time-of-day-dependent manner [47]. Recently, melatonin synthesis has been suggested to interact with core circadian mechanisms [48].

Neurohormone MTG is an anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuro-protectant agent. It plays numerous physiological roles as a modulator of the biological clock. Specifically, the sleep-wake cycle regulation of circadian rhythms, protection of mitochondria [49-55]. Furthermore, MTG is also believed to be involved in the modulation of learning and memory also enhance cognitive capacity [56-58], via its binding to receptors widely distributed throughout the brain [59-62].

Researchers also indicate that MTG may exert particular therapeutic effects in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease [63-65] by protecting against neurotoxicity induced by amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides [66-68]. Interestingly, some studies have shown that MTG attenuates pyramidal neuronal cell damage in the hippocampus in global cerebral ischemia [69-75].

Melatonin and memory formation

As the levels of melatonin and CREB expression gradually decrease with age in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex [76-80]. Both are considered with the age-dependent memory formation or memory preservations or cognitive deficits mechanism [81].

To date, melatonin administration shows memory enhancement effects in multiple memory and age-related or impaired animal models [74,82-85].

The activation of CREB via phosphorylation in the hippocampus is an important signalling mechanism for enhancing memory processing. CREB is a well-studied transcription factor that mediates intracellular signalling events that regulate the circadian rhythms of memory [86], long-term memory [87], and a variety of downstream effectors in the hippocampus and enhance hippocampal memory processing [88].

Melatonin has been shown to phosphorylate CREB in animal models [89,90]. That may enhance memory, but the signalling mechanism between melatonin and CREB is hitherto unestablished.

Melatonin receptors have been identified (in vivo consideration) in the hippocampus of various animals [82-94], and activated via specific receptors in the hippocampus cells. Melatonin has been identified as a protector of pyramidal cells in the hippocampus and have long-term potentiation from damage in the case of non-receptor mediated actions [41]. Overall, the protective action of melatonin may be receptor-independent via free radical generating mechanisms [80] related to learning and memory [50].

To justify the inner mechanism, the in vitro assessment in HT-22 cell line infers that melatonin treatment increases the level of Raf, ERK, p90RSK, CREB, and BDNF expression by consequence of phosphorylation. The expressed genes are associated with long-term memory formation and consolidations and referred that melatonin is associated with a variety of signaling mechanisms including the ERK and MAPK pathways (Figure 1) [82,95].

In recent times, a group of scientists from Tokyo Medical and Dental University found that melatonin and its metabolites [N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AFMK) and N1-acety-l5-methoxykynuramine (AMK) in the brain] promote the formation of long-term memories in mice and protect against cognitive decline [96].

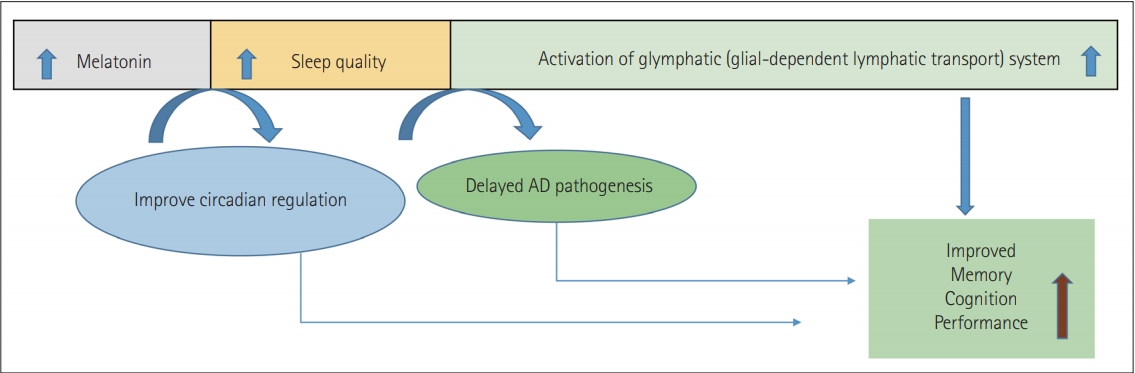

Melatonin in the glymphatic system and cognitive functioning

It has been reported that melatonin is attenuated during the ageing process and the patients with AD had a substantial reduction of this hormone. However, melatonin supplementation was found to minimize Aβ neurotoxicity and formation while enhancing cognitive efficiency [97-103].

Early treatments with melatonin may be one of the most effective methods for developing approaches to postpone or avoid Aβ and memory problems at this stage of the disease [103]. Melatonin crosses the blood-brain barrier in direct contrast to traditional antioxidants, is relatively free of toxicity, and is a possible therapeutic candidate in AD care, possibly due to enhancing the quality of sleep and clearance of Aβ42 plaque by increasing the efficiency of the glymphatic system. Specifically, by promoting the glymphatic system function, deep sleep is essential in this clearance phase [104-108].

By the continuous interchange of fluids, the glymphatic system is a well-established waste clearance pathway of the brain. A primary driver of glymphatic clearance is sleep [109-112]. Nevertheless, research has started to appear on a wealth of other lifestyle choices such as sleep quality, amount, physical activity, body posture improvements, omega-3, chronic stress, intermittent fasting, and low alcohol doses. Glymphatic activity is gradually decreased with AD and ageing due to the loss of the water channels, AQP4 which facilitates fluid flow, with impaired interstitial solute clearance and increased aggregation [113,114].

Interestingly, a significant number of AD patients report increasing sleep disturbances along with the severity of the disease. AD and sleep disturbances signify a bidirectional relationship found before AD’s clinical onset, where sleep disturbances occur with the frequency of Aβ, but often cause soluble Aβ to increase. Overall, the findings support the hypothesis that it may reduce AD development due to melatonin’s ability to promote sleep and act as an antioxidant [115-117]. It, therefore, increases cognitive function and decreases neuropathology in the model of mice, likely through glymphatic system activation (Figure 2) [118-122].

SLEEP AND COGNITION

Sleep cycle

Sleep is a multidimensional biochemical process to maintain homeostasis. It is categorized as a decline in consciousness and body responses to external stimuli, along with some brain electroencephalogram changes [123,124]. Complex shifts in the pattern of neuronal firing and neurotransmitter release [125] are followed by the transitions from wake up to sleep and between sleep phases. Rapid eye movement sleep (REM) and non-rapid eye movement sleep (n-REM), which alternate throughout the night in a roughly 90-minute cycle. n-REM sleep is further divided into three stages (Figure 3) [126].

Neurobiology and biochemistry of sleep and wakefulness

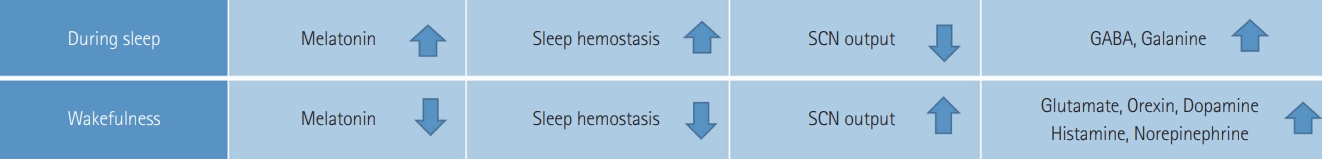

To understand the relationship between sleep and cognition, it is required to find the particular region of the brain, which is involved in the sleeping and waking process. Richter’s studies on the lesion inferred that a “master” clock is located in the hypothalamus [127]. Loss of behavioural and endocrine rhythms resulted in ablation of the SCN. Sleep homeostasis prevails at bedtime and SCN output is decreased, thus promoting sleep, while SCN output increases with little to no sleep pressure in the morning, thus promoting alertness [128-132].

Three primary factors affect the normal sleep and wake cycle: intrinsic circadian rhythm, behaviour of homeostatic inner sleep, and external factors [132-134]. Melatonin and light exposure are the core regulators of circadian rhythms. A few hours before bedtime, the melatonin level upsurges and assists sleep, and light exposure decreases melatonin secretion and disrupts sleep or improves wake-up.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid, galanin, and adenosine are the sleep-promoting neurotransmitters. While orexin (hypocretin), glutamate, norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, histamine, acetylcholine, and histamine are the key neurotransmitters that promote wakefulness. Wakefulness is a moment when a neurophysiological perspective is formed. Through activation of reticular brain stem formation, secretion of norepinephrine, serotonin, and acetylcholine by the pons; and release of histamine by the posterior hypothalamus. In the lateral and posterior hypothalamus and its peptides and hormones, orexin/hypocretin neurons play a vital role in controlling eating, reward-seeking, reacting to arousal and metabolic signals to change vigilance states, addiction and stress; and in stabilizing both wakefulness and sleep (Figure 4) [135-143].

Differences between the changes in biochemical and physiological factors of sleep and wakefulness. SCN: suprachiasmatic nuclei.

Production of n-REM sleep is coordinated by the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus in the anterior hypothalamus. During n-REM sleep, norepinephrine, serotonin, acetylcholine, and histamine release are decreased. The initiation of REM sleep is coordinated by communication between aminergic neurons, which produce norepinephrine, serotonin and histamine, and cholinergic neurons. During REM sleep, the aminergic neurons become nearly silent, while cholinergic neurons become highly active. These profound changes in a neurophysiological state seen across the sleep cycle, with the change of both in the activity of neuronal networks and the neurochemical milieu of the brain, suggest that sleep evolved as a period of altered cognitive processing [144,145].

Models of memory processing in sleep

A significant correlation between sleep and cognitive processing has been well established over the past few years. In consolidating various forms of memory, sleep plays an important role and leads to reflective and inferential thought. Although the mechanism by which types of memories are stored in sleep remains unclear, numerous conceptual models have been presented.

The association of sleep and cognition primarily correlates three distinct dimensions: 1) the effects of sleep deprivation on cognition, 2) the influence of sleep on declarative and non-declarative memory consolidation, and 3) some proposed models of how sleep facilitates memory consolidation in sleep.

Wilson and colleagues [146,147] conducted a neuronal level experiment on brain function in rats, which unveiled underlying query regarding the processes that occur in the brain during sleep and enables memory. They proposed the principle of “replay” of brain activity, as well as the re-appearance in sleep of brain activity that occurred during prior wakefulness and learning. They observed that during a spatial behavioural task, hippocampal cells that fired together during subsequent slow-wave sleep tended to replicate sequences of neuronal firing that indicate motion along a spatial path.

By measuring cerebral blood flow with positron emission tomography, Peigneux et al. [148] investigated regional brain activity in humans. They discovered that when subjects learned a route in a virtual town, hippocampal areas that were activated in humans showed increased activation during subsequent slow-wave sleep. Furthermore, the hippocampal activity also seen during slow-wave sleep was associated with the next day’s task results. A similar effect, in a serial response time task, was also confirmed by Maquet et al. [149].

In subjects who had recently completed the task, several regions of the brain that were active during the execution of the task were significantly more active during REM sleep than in those who had not trained on the task. These outcomes can help researchers to conclude that during sleep, recently encoded memories are reactivated and “replayed”.

The theory of synaptic homeostasis, which suggests that a process of synaptic downscaling occurs during sleep, particularly slow-wave sleep, is contrary to the notion that replaying during sleep improves memories [150,151].

As a means of conserving energy and space within the brain, total synaptic strength in the cortex is drastically reduced during this process. Such downscaling could indirectly gain learning and memory, according to some formulations of this model.

TIMING OF FOOD AND SLEEP ON COGNITION

Many aspects of cognition, including excitement, concentration, and working memory, are known to be affected by the timing of sleep. In rodents, sleep deprivation has been reported to decrease contextual fear memory in the first 5 h after training, despite otherwise sufficient sleep, but does not affect tone-cued fear memories [152,153].

Spontaneous object recognition studies have shown that both object-recognition and object-location memories are impaired by 5–6 h of sleep deprivation after training [154-157], with an apparently crucial window at 3–4 h [158]. Another test, which relies on undesired water immersion to enable animals to find a secret medium for observing the process of spatial learning and is responsive to hippocampal injury, is also essential for other brain regions and strategies [159].

Sleep architecture is also essential for memory, in addition to sleep duration. Humans sleep once a day in a consolidated bout and advance throughout the night over several periods of REM and NREM sleep. Daytime activity is compromised if this is fragmented and increased sleepiness occurs [160]. This phenomenon is also observed in a study conducted by Gupta et al. [161]. When comparing the 4 h drive to the 20 h drive, cognitive performance decreased during the night, with driving safety being questionable, including difficulty driving in the middle of the lane, adhering to the speed limit, and crashing.

Throughout the day and night, rodents sleep in numerous brief bursts consisting of both REM and n-REM sleep, with a sufficient amount of sleep during the light period, mainly due to increased sleep duration during the day [162].

Disturbing daily waking sleep architecture prevents the usual completion of sleep bouts, resulting in increased sleep pressure despite no improvement in the overall period of sleep [163]. Fragmentation of sleep also influences mechanisms of cognition. There are low learning and retention in the Morris water maze for mice subjected to sleep fragmentation for 15 days [164]. These studies indicate that disrupted sleep may lead to impaired performance in specific cognitive processes, even though sleep timing and overall sleep duration can remain comparable.

Data from mice experiment (missing GluA1) may provide some insight into the effects of these synaptic plasticity changes that take place during sleep. GluA1 deficient mice, such as the Morris water-maze, display unimpaired success on associative, long-term memory tasks. These species showed selective short-term deficits to recently experienced stimuli [165,166].

These results indicate that the levels of synaptic GluA1 increase during waking, like an ongoing habit and a decrease in attention. This hypothesis suggests sleep can be necessary for restoring attentional efficiency [167].

There are multiple effects on cognition based on the time of food. Numerous studies have been conducted regarding this issue. Among these, in particular, eating a meal or not eating during the night shift to observe the success of attentive and careful driving. The performance of those who did not eat the meal during the night shift was better than the others [168].

Additionally, on the night shift, eating a big meal impairs cognitive efficiency and sleepiness beyond the consequences of nighttime alone. Shift workers can opt for a snack at night for enhanced efficiency [161].

In conclusion, while the cognitive function is unquestionably affected by the disruption of sleep and food timing, the specific cognitive processes affected and the underlying mechanisms involved are not straightforward. However, researchers should always be aware that due to a concomitant disruption of sleep and food timing, effects on cognition could arise.

ROLE OF SHIFT WORK, ARTIFICIAL LIGHT, AND JET LAG

There are multiple examples in our current world where lifestyle clashes with our internal biological clocks, including shift work and jet lag. Besides, artificial light results in light emission from electronic devices such as phones, tablets, and computers at inappropriate times of day, like a light at night, as well as exposure to light. As a result, there is rising concern about the effects on human health of circadian disturbance and aberrant light exposure, including impacts on metabolism, cardiovascular function, mental health, and even cancer risk [169-171].

A good number of studies have examined the impact of aberrant light exposure on cognitive performance. Rodents are used under the irregular light and dark (LD) cycles to investigate the underlying mechanisms of circadian disruption and correlation of adverse health conditions. During the usual subjective night, some result in light exposure; while others result in a mismatch between internal circadian time and external ambient time requiring a constant change of phase. It has been proposed that the negative effects of circadian disruption could be the reason for this mismatch [169].

To simulate the sudden change in time zones created by jet lag, shifting the LD period under which animals are housed has been used. A single advance or pause in the LD period is usually involved in acute jet lag protocols. Besides, persistent jet lag, which includes frequent LD cycle changes, has also been used as a circadian disturbance model [172].

Approximately 15% to 18% of all workers in Europe and the United States work on night shift schedules [173], and 15–30% in Korea [174]. Night shift work has become a common occupation. It was calculated that the exposure levels of artificial light at night (ALAN) to shift staff at night ranged from 50 lx to 100 lx, often reaching 200 lx [175]. At night, exposure to ALAN leads to melatonin suppression, clock gene expression changes, and sleep misalignment [174]. Acute suppression of melatonin after 1 hour of light exposure to the retina light inhibits sensitivity to melatonin by approximately 5% at 30 lx, 15% at 100 lx, 35% at 300 lx, and 55% at 1000 lx. After exposure to over 10000 lx, maximal suppression was 70% [176,177].

When tested at waking time, night shift nurses reported significantly lower levels of the melatonin metabolite urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin (aMT6s) than day shift nurses. Night shift workers, however, did not exhibit peak levels of melatonin while sleeping during the day [178]. During the night, the peak melatonin levels occurred among nurses working rotating shifts, and when the nurses encountered ALAN levels below 80 lx, melatonin levels were not different between night and day shift nurses [179]. In night shift workers, a decrease in melatonin suppression was observed, from 40.6% to 22.9%, as the number of recent night shifts increased, indicating a phase shift or adaptation to night work [180].

Together, these findings show that using both acute and chronic jet lag protocols, ALAN, and night shift result in subtle changes in cognitive processes. However, given the effect of these protocols on both sleep fragmentation and arousal, the mechanisms by which cognitive processes are influenced are difficult to establish.

CONCLUSION

For a long time, melatonin was thought to be one of the possible inhibitors of long-term memory formation. However, after extensive research, it has been established as a neuroprotective hormone that regulates oversleeping, disease progression, circadian rhythms, and cognitive processes.

At a glance, initiation of quality sleep, clock gene regulation, circadian rhythm optimization, glymphatic system induction, and melatonin are considered a multidirectional compound to ensure body hemostasis and memory consolidation.

Acknowledgements

None

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Md. Arifur Rahman Chowdhury, Md Mazedul Haq, Chandresh Sharma. Data curation: Md. Arifur Rahman Chowdhury, Md Mazedul Haq. Formal analysis: Md. Arifur Rahman Chowdhury, Md Mazedul Haq. Methodology: Md. Arifur Rahman Chowdhury, Md Mazedul Haq, Chandresh harma. Project administration: Md. Arifur Rahman Chowdhury, Md Mazedul Haq, Chandresh Sharma. Resources: Md. Arifur Rahman Chowdhury, Md Mazedul Haq, Chandresh Sharma. Software: Md. Arifur Rahman Chowdhury, Md Mazedul Haq, Chandresh Sharma. Supervision: Chandresh Sharma. Validation: Chandresh Sharma. Visualization: Narayan Kumar, Chandresh Sharma. Writing—original draft: Md. Arifur Rahman Chowdhury, Md Mazedul Haq, Chandresh Sharma. Writing—review & editing: all authors.