Role of Depression and Anxiety As Mediators Between Insomnia Symptoms and Suicide Ideation in Patients With Adjustment Disorder

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether insomnia can independently affect suicide ideation or whether insomnia affect suicide ideation by mediating depression or anxiety in adjustment disorder (AD).

Methods

Electronic medical records were retrospectively reviewed for 65 patients with diagnosed AD visited an outpatient clinic between January 2018 and December 2020. Measurements include the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2). Statistical analyses were performed to assess relationship between insomnia and suicide ideation in AD and the mediating role of depression or anxiety in this association.

Results

During 3 years of study period, of the AD patients, 37 (57%) were male and 28 (43%) were female. Among them, 45 (69.2%) and 23 (35.4%) had clinically significant symptoms of insomnia (ISI ≥15) and suicide ideation (MMPI scale score ≥70), respectively. In a mediation model using depression and anxiety as mediating variable, there were significant effects of insomnia on depression (t=5.55, p<0.001) and anxiety (t=6.21, p<0.001) and of depression (t=5.70, p<0.001) and anxiety (t=3.54, p<0.001) on suicide ideation. Total effect of insomnia on suicide ideation was statistically insignificant, suggesting complete mediation.

Conclusion

A significant association with suicide ideation was observed in the case of insomnia accompanied by depression and anxiety. Therefore, in patients with AD who complain of insomnia, symptoms of depression and anxiety should be evaluated by clinicians with active intervention for suicide ideation.

INTRODUCTION

Adjustment disorder (AD) is a common psychiatric disorder in the clinical field, with an estimated prevalence in the general population of 2%–8% [1]; approximately 10%–30% of patients who visit the Department of Psychiatry have ADs. AD is diagnosed in as many as 50% of patients with specific medical problems or stress [2]. In general, with appropriate treatment and intervention, the prognosis for AD is good. However, regarding the course and prognosis of AD, it is important to note that patients with this disorder may have an increased risk of suicide. In previous report on outpatient adolescents, 25% of those with AD had suicidal behaviour [3]. According to another study, a diagnosis of AD was reported in 53.5% of patients who visited the emergency room for self-mutilating behavior [4]. AD were reported for 77% of patients with serious or high-risk suicide attempts and 50% of low-risk trials [5]. Therefore, in treatment of all patients with AD, the risk of suicide should be thoroughly assessed from the start of treatment.

Depression is often known as the primary risk factor for suicide ideation, and there are several risk factors other than depression, one of which is sleep problems. A relationship between sleep and suicide ideation has been reported in several studies [6-9], and it has been suggested that sleep problems, such as difficulty in waking up and difficulty in maintaining sleep, increase the risk of suicide [10]. However, previous studies have shown an association between sleep problems and suicide independent of depression or anxiety symptoms [11,12], while other studies showed that the association between sleep and suicide ideation did not appear independently of depression or anxiety symptoms [13]. In addition, because most studies on the relationship between sleep and suicide ideation have been conducted with depressed patients or the general public, evidence regarding the relationship between sleep problems and suicide in patients with AD in which disturbance of sleep is a significant symptom [14] and are common in clinical settings and disturbance, is insufficient.

Therefore, in this study, targeting patients with AD who visited Konkuk University Hospital outpatient department of psychiatry, we attempted to determine whether the association between insomnia and suicide ideation also appeared in patients with AD, and if there was a relationship, whether insomnia can independently affect suicide ideation or whether insomnia symptoms affect suicide ideation by mediating psychiatric symptoms such as depression or anxiety. This is because depression and anxiety symptoms are common in AD. We hypothesized that depression and anxiety would mediate the relationship between insomnia and suicide ideation in patients with AD.

METHODS

Paricipants

A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted in Konkuk University Hospital, Korea. A total of 65 patients, who were newly diagnosed with AD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) [15] from January 2018 to December 2020, were included in the study. All patients were assessed using a self-reported questionnaire based on illness history and psychiatric and medical examinations. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Konkuk University Hospital (IRB number: KUMC 2022-01-021), and written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Measures

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)

The ISI is a simple self-report questionnaire measuring a patient’s perception of insomnia severity [16]. The Korean version of the ISI has been used to assess sleep disorders in the Korean population and has been shown to be a reliable and valid assessment tool. It consists of 7 questions stating: 1) Difficulty in falling asleep; 2) Difficulty in staying asleep; 3) Problems of waking up too early; 4) How satisfied are you with your current sleep pattern?; 5) How noticeable to others do you think your sleep problem is in terms of impairing the quality of your life?; 6) How worried are you about your current sleep problem?; 7) To what extent do you consider your sleep problem to interfere with your daily functioning currently? Each question is rated using a 5-point Likert scale from 0 to 4 (e.g., 0=no problem; 4=very severe problem). The sum of the answers to these 7 questions yields a total score from 0 to 28. The cut-off score required to distinguish patients with insomnia in the Korean version of the ISI is 15.5 points [17]. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) reported from the validation study was 0.92 [17].

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)

The BDI is a 21-item questionnaire designed to evaluate the severity of depressive symptoms during the previous 2 weeks from the time of administration. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3. The total score ranges from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptom. The BDI was originally developed by Beck et al. [18]. In accordance with changes in the criteria for diagnosing depressive symptoms in DSM-IV, it was revised to BDI-II in 1996. It was validated in Korean, and 13 points were presented as a cutoff for minimal depression [19,20]. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) reported from the validation study was 0.94 [19].

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

The STAI is a 40-item self-report questionnaire, 20 items assigned to each of the State Anxiety Scale (S-Anxiety) and the Trait Anxiety Scale (T-Anxiety) subscales, to measure the presence and severity of current symptoms of anxiety and a generalized tendency to anxiety. This measure has two subscales. First, the S-Anxiety evaluates the current anxiety state by asking how the respondent feels now using items measuring subjective feelings of anxiety, tension, nervousness, worry, and activation/arousal of the autonomic nervous system. The T-Anxiety assesses relatively stable aspects of “anxiety tendencies,” including general states of calm, confidence, and stability [21]. Scores on each subtest range from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating higher anxiety. For the S-anxiety scale [22,23], cut points of 39–40 have been proposed to detect clinically significant symptoms, whereas other studies have suggested higher cut scores of 54–55 for the elderly [24]. In this study, we used only STAI-S as mediating factor [25]. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) reported from the Korean validation study was 0.91 [26].

Suicide ideation

To assess the severity of suicide ideation, we used the 5-item DEP4 scale in the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2) (#303, 454, 506, 520, 546). The DEP4 is the one of the 4-component DEP (Depression) Content scale, which is identified by Ben-Porath and Sherwood [27]. The items of the scale are thought to assess “a pessimism about the future that is so dire as to support a wish to die and thoughts of suicide [28,29].” The participants are requested to answer in true/false format affirmative statements (1=true, 0=false), and the sum of the raw scores are converted to demographically-adjusted T-scores with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. A cut-off of 70 T-score was used to differentiate those with high levels of suicidal ideation [30]. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of the DEP Content scale was 0.89 [31].

Statistical analyses

As a result of the data analysis, data on STAI-S and ISI were omitted for two participants, and 65 participants were used for the analysis. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and PROCESS Macro 3.4.1 [32]; demographic and descriptive statistics were calculated first. Pearson’s correlations for ISI, BDI-II, STAI-S, and suicidal ideation were then calculated. Finally, using PROCESS Model 4 [32], mediational analysis was performed using BDI-II and STAI-S as mediators between ISI and suicidal ideation. Mediational analysis produces direct, total, and indirect effects, where significant indirect effects indicate that effects of insomnia on suicidal ideation through the mediator is significant. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals are produced for indirect effects to evaluate their significance.

RESULTS

General characteristics of subjects and suicide ideation

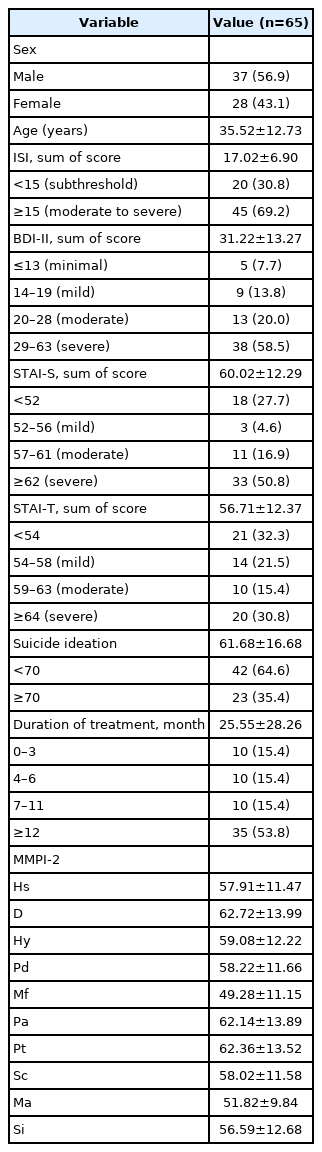

A summary of the basic characteristics of the observed variables is shown in Table 1. The participants were 57% male and 43% female (male:female=37:28) and the mean age was 35 years (mean± standard deviation=35.52±12.73). Treatment was administered for 0–3 months in 11 participants, 4–6 months in 10 participants, and 7–11 months in 10 participants, whereas treatment continued for more than 12 months in 36 participants.

In the case of insomnia, an ISI score of 15 or higher was reported for 69.2% of participants, indicating clinically significant symptoms of insomnia. Minimal depressive symptoms were reported for approximately 7.7% of the BDI-II score, whereas a score of 29 or higher was reported for 58.5% of participants, confirming that they had severe depression. In addition, it was found that 50.8% and 30.8% of the participants complained of severe anxiety through STAI-S and STAI-T, respectively, and in the case of suicidal thoughts confirmed through the MMPI scale score, 35.4% of the participants had suicidal thoughts.

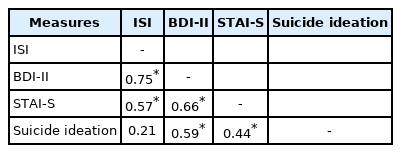

Association between depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and insomnia

The results of Pearson’s correlation analysis are shown in Table 2. Considering the results, the correlation coefficient between ISI and BDI-II was statistically significant at r=0.75 with a significance level of p<0.001, and the correlation coefficient between ISI and STAI_S was statistically significant at r=0.57 with a significance level of p< 0.001. There was a significant correlation between STAI-S and BDI-II and the correlation coefficient was 0.66 (p<0.001). In the case of suicidal ideation, there was no statistically significant association with ISI, however, there was a statistically significant association with BDI-II and STAI-S with r=0.59 and r=0.44, respectively, with a significance level of p<0.001.

Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted for effects of age, sex, ISI, BDI-II, STAI-S, and STAI-T on suicidal ideation as outcome. The model was significant at p<0.001, and explained about 40% of the variance of suicidal ideation (adjusted R2=0.40). Depression, as measured by BDI-II, and trait anxiety, as measured by STAI-T, significantly contributed to suicidal ideation (β=0.52, standard error; SE=0.18, p=0.001; β=0.32, SE=0.18, p=0.02, respectively). The results are summarized in Table 3.

Mediation analysis

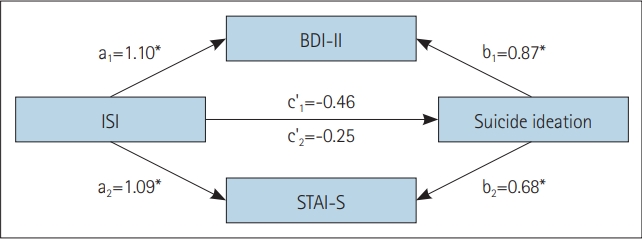

A mediating analysis model where depression and anxiety mediate the relationship between sleep problems and suicidal thoughts is shown in Figure 1. As discussed earlier, in the case of suicidal thoughts there was no statistically significant correlation with insomnia itself (Table 2). However, there was a significant effect of insomnia on depression (t=5.55, p<0.001; a1 path) and anxiety (t=6.21, p<0.001; a2 path), and of depression (t=5.70, p<0.001; b1 path) and anxiety (t=3.54, p<0.001; b2 path) on suicide ideation based on unstandardized regression coefficients. Since the bootstrapped 95% confidence interval did not contain zero (0.23, 0.68), the indirect effect was significant. Furthermore, the main effect of insomnia on suicide ideation was insignificant, after controlling for the effect of depression and anxiety, suggesting complete mediation.

Mediational model containing BDI-II and STAI-S as mediators. a, effect of insomnia on the mediator; b, effect of the mediator on suicide ideation; c', direct effect of insomnia on suicide ideation after controlling for mediators. Subscript ‘1’ indicates values for the BDI-II model. Subscript ‘2’ indicates values for the STAI-S model. *p<0.001. ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; STAI-S, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory--State.

The results of the mediation analysis are shown in Table 4; it can be confirmed that the mediating of depression and anxiety symptoms has a significant effect on suicidal ideation.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicide ideation in patients with AD. In addition, if there was an association, we attempted to determine whether the association is mediated by symptoms of depression and anxiety. The male to female ratio was similar for participants in this study, and those who continued treatment for more than 12 months accounted for the largest proportion. In addition, clinically significant insomnia symptoms were observed in approximately half of the participants, 58.5% and 50.8% of the participants complained of severe depressive symptoms and severe anxiety, and 35.4% of the participants complained of suicidal thoughts.

Participants’ insomnia symptoms showed a significant association with depression and anxiety. As reported in several previous studies, insomnia often accompanies depression, and depression and insomnia are bilaterally related [33]. In other words, insomnia is a typical symptom of depression, and at the same time, insomnia is an independent risk factor for depression. Therefore, in the case of patients with depression and insomnia, treatment for both depression and insomnia should be administered simultaneously from the beginning of treatment, and depression may recur without treatment of persistent insomnia [34].

In the case of suicide ideation, which we attempted to investigate in this study, as reported in previous studies, there was a significant association with depression and anxiety, but it was confirmed that there was no significant association with insomnia alone and only the case of mediating depression and anxiety showed a significant association. Several previous studies have reported that the risk of suicide ideation is higher with sleep problems in both adults and adolescents [35-38]. Accordingly, it was possible to conclude that there is a relationship between sleep disturbance and suicide ideation [13]. In particular, a previous study confirmed that the risk of suicide ideation was higher if there was a sleep problem in the case of depression and a previous psychiatric medical history [39-41]. This is consistent with the fact that depression is a strong risk factor for suicidal thoughts [42].

However, a previous study also confirmed that the risk of suicide ideation increases even in general adults without a history of psychiatric treatment if they have sleep problems, such as lack of sleep [6,11]. Because insomnia is a symptom that accompanies depression, several studies have examined the question of whether insomnia increases the risk of suicide ideation, or whether insomnia itself can increase the risk of suicide ideation. In this study, evaluation of patients with AD found no association with suicide ideation if only complaining of insomnia symptoms, and there was a significant correlation with suicide ideation if insomnia was accompanied by symptoms of depression and anxiety. In other words, in the case of patients with AD who have sleep problems, the risk of suicide ideation increases when symptoms of depression accompany symptoms of anxiety. Therefore, when a patient with AD complains of sleep problems in the clinical setting, treatment should not focus on only the insomnia symptoms, but the depression and anxiety symptoms should be evaluated together. In addition, it can be concluded that, when symptoms of depression accompany symptoms of anxiety, an evaluation of suicidal thoughts must be performed, and active intervention is necessary.

The limitations of this study include the following. First, it is a retrospective cross-sectional study in which data are collected at a single time point to investigate the relationship between disease and other variables of interest. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether it is a result of temporal exposure or exposure according to a result. Secondly, this study used data from a relatively small number of participants and thirdly, suicide ideation was calculated from the MMPI without asking directly. Therefore, in future research, an evaluation of the relationship between sleep problems and suicide ideation should be conducted through evaluation of depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with AD who visited the hospital with insomnia as the primary symptom; suicide ideation should then be evaluated in a direct and detailed manner.

Notes

Funding Statement

None

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Seung-Ho Ryu, Jee Hyun Ha. Data curation: Seolmin Kim. Formal analysis: Eun Jung Cha. Investigation: Hong Jun Jeon. Methodology: Seolmin Kim, Eun Jung Cha. Project administration: Seung-Ho Ryu. Software: Eun Jung Cha, Seolmin Kim. Supervision: Seung-Ho Ryu, Kyoung Hwan Lee, Doo-Heum Park. Visualization: Kangyoon Jung. Writing—original draft: Kangyoon Jung. Writing—review & editing: Seung-Ho Ryu, Hong Jun Jeon, Kyoung Hwan Lee.